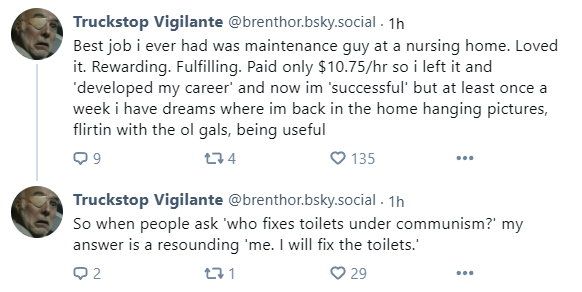

We're in the middle of a plague

[Click to listen to the article, and support the Canary]

The NHS killed Sophia Mirza on 15 November 2005. Sophia lived with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS). In July 2003, psychiatrists got cops to smash the door into Sophia’s home down and forcibly take her to a secure psychiatric unit, where she was imprisoned against her wishes for two weeks before a tribunal ordered her release. This ultimately led to her death.

In January 2024, Olivia Jane Mott travelled from the UK to Dignitas in Switzerland to end her own life. She lived with ME. On 27 March 2024, Lucy Mayhew died. She lived with ME.

Right now, Millie McAinsh is dying in an NHS hospital because doctors don’t believe her illness is real. They previously sectioned her under the Mental Health Act, enforced Deprivation of Liberty Safeguarding (DoLS) measures on her, and are forcing her to have treatment she doesn’t want. Millie lives with ME. So does Karen Gordon – in an almost identical situation to Millie.

So, nearly 20 years after the NHS killed Sophia, people living with ME are still dying while the state either lets them or actively brings it about. The obvious question is why? Well, the Canary has extensively documented the answer to that.

However, the less obvious but perhaps more necessary question is why are we allowing this to happen?

ME/CFS: inaction, inaction, inaction

The answer to that is a complex melting pot of issues, including (but not limited to):

-

ME/CFS is still poorly misunderstood – or rather, made out by the medical profession, the state, and media to be.

-

The ME community exists in the most part of people online who are a) clued-up on the issues, and b) have a diagnosis in the first place. Read this about fibromyalgia and ME diagnoses.

-

People have their own political views which play into how they respond to situations of injustice, abuse, and discrimination. We’re a mixed bag of left, right, and no wing.

-

The full force of the media and state has been consistently putting its boot on the neck of the ME community.

-

Charities and Disabled People’s Organisations (DPOs) within the community tend to work to their own agendas – not collectively.

But one of the most pressing one is the community’s inability, and in some cases unwillingness, to protest.

Where are the protests? Where are the occupations?

Campaigning, protesting, and taking direct action have throughout history been the way ordinary people have brought about change. Be under no illusions: it is NOT politicians, charities, or the state who do – and even when they have, it’s because people like you and me have forced them to.

However, this has always been the circle that (until this point) cannot be squared: severely chronically ill and disabled people cannot easily protest. They’re bodies often won’t let them. So, they need allies and advocates to do it for them.

Yet where are the protests from non-chronically ill allies?

I seem to recall some shoes being placed outside the Department of Health and the BBC a few years ago (I’m being wry – I was there). Otherwise, the ME community doesn’t protest – unlike nearly every other marginalised group in the UK.

For example, me and my partner Nicola were literally blocking one of the main arterial roads into Westminster with other disabled people a few weeks ago. It was over benefit-related deaths. Cops kettled disabled wheelchair users and threatened people with arrest.

Yet that pales in comparison to the tens of thousands of people who have died under the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) regime; one the UN said caused “grave” and “systematic” violations of chronically ill and disabled people’s human rights.

ME/CFS: we literally have nothing to lose

So, why has the ME community not embraced direct action and protest as part of its strategy?

I can’t safely answer that. That’s for all of us to reflect on. I think there’s elements of class within this. Many marginalised communities are also socioeconomically marginalised by the state. That is, they’re poor in every sense. Specifically, not only does the state marginalise you for, say, your ethnicity or disability, it also marginalises you economically.

As American writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin summed up:

The most dangerous creation of any society is the man who has nothing to lose.

Black people, disabled people, refugees, non-working people all have the least to lose – therefore, civil disobedience isn’t as daunting.

The ME community needs to fully recognise its own marginalisation and take that to its very core. Millie is a case in point for us all: she has little to lose, now – and things can’t get much worse.

Shut up and sit down

There’s another element to this lack of protest and direct action.

Regarding Millie, I keep seeing comments, and am also being told privately by quite well-known figures in the ME community, that:

Things are going on behind the scenes.

But:

You shouldn’t really do ‘x, y, z’ as it will make the situation worse for Millie.

And:

The ME/CFS charities are working with Millie’s family.

If I hear another comment along these lines I’ll scream.

Whatever the ME charities and those in the self-appointed (which they are, unless people with ME took a vote on it that I missed) upper echelons of the community have been doing since the NHS killed Sophia on 15 November 2005 HAS NOT WORKED. If it had, Millie and Karen would not be in the situation they’re in.

Olivia would still be alive.

Lucy would still be alive.

And Merryn, Maeve, and Kara Jane would still be alive.

Nothing has worked in 20 years.

Labour MP Debbie Abrahams once said in parliament regarding the tens of thousands of disabled people that have died on the DWP’s watch:

Does the minister think that it is unacceptable that any government policy should cause their citizens to take their own life or to die? If he does, should there not be a moratorium on this policy until it is got right? Surely one death is one too many.

Why has the ME community for decades accepted so many deaths of its own?

It is past time that the ME community realised that we are perpetually going round in circles, doing the same things over and over again – and that they are not working.

It is also past time that the ME community stopped allowing certain gatekeepers to govern how it conducts itself and how it responds to the abuse medical professionals and the state inflicts on its members; abuse that is not inflicted on those same gatekeepers.

And it is past time that the ME community stopped putting its faith in charities who take hundreds of thousands – sometimes millions – of pounds every year in donations and yet demonstrably achieve absolutely nothing with it.

That is, the ME community and its allies in other chronic illness communities like long Covid need to take matters into their own hands. Enough really is enough this time.

Get our acts together, or we are as good as dead

Larry Kramer was the founder of direct action group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). Him and his supporters advocated for disruptive civil disobedience in the face of the HIV/AIDS crisis that was sweeping the US in the 1980s.

ACT UP members repeatedly got arrested for actions like blocking roads. However, Kramer and his group changed the course of HIV/AIDS: how it was viewed by the public, how it was represented by the media, and ultimately how it was treated by medical professionals.

He once said:

I was trying to make people united and angry. I was known as the angriest man in the world, mainly because I discovered that anger got you further than being nice. And when we started to break through in the media, I was better TV than someone who was nice.

The ME community has been “nice” for far too long. It’s not like we’re complaining about potholes, tree-felling, or London’s ULEZ scheme. We’re fighting against the state-run health service literally killing members of our community. Yet, all those three other examples I gave have seen bigger – and often more civilly-disobedient – protests than the ME community has ever engaged in.

Crucially, though, Kramer famously screamed in the middle of a meeting of AIDS activists who were arguing among themselves and utterly disorganised:

Plague! We are in the middle of a plague! And you behave like this! Plague! 40 million infected people is a plague! Until we get our acts together, all of us, we are as good as dead.

So, get their act together they did.

The ME/CFS community needs it’s own ‘plague’ moment

The ME community’s “plague” moment should have been Sophia’s killing in 2005.

But it wasn’t.

It should have happened at the start of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic.

But it didn’t.

It should have been Merryn’s, Maeve’s, Kara Jane’s, and every other person with ME’s deaths because of how the system has treated them.

But it wasn’t.

So, I ask you this: is it going to take the NHS killing Millie for the ME community to have its “plague” moment and finally ‘get its act together’? Because that cannot happen.

Millie’s story – ending with her returning home to safety – must be a watershed moment for all our sakes. It must be a moment where we as a community stare at ourselves in a mirror until our eyes collectively bleed and ask ourselves whether what we are, and have been, doing is right – and if we should continue with it.

And I can tell you now: the answer to those questions is ‘no’.

i would remove the tracker in your link (the

?si=).