Synopsis

Remember back in "The Naked Time," the Enterprise was thrown back in time a bit by excessive warp speed. This was used (by my count) three more times: "Tomorrow Is Yesterday," "Assignment: Earth" (TOS 2x26), and The Voyage Home.

On this occasion, time travel was unintentional, and the Enterprise is spotted on Air Force radar. A jet is scrambled to investigate, and the Enterprise accidentally destroys it with its tractor. They beam the pilot aboard, and get caught in a conundrum: do they send USAF Captain John Christopher back to Earth, knowing he knows the future? Worse, it turns out Christopher's son will be an astronaut himself, so they can't bring Christopher back to the future.

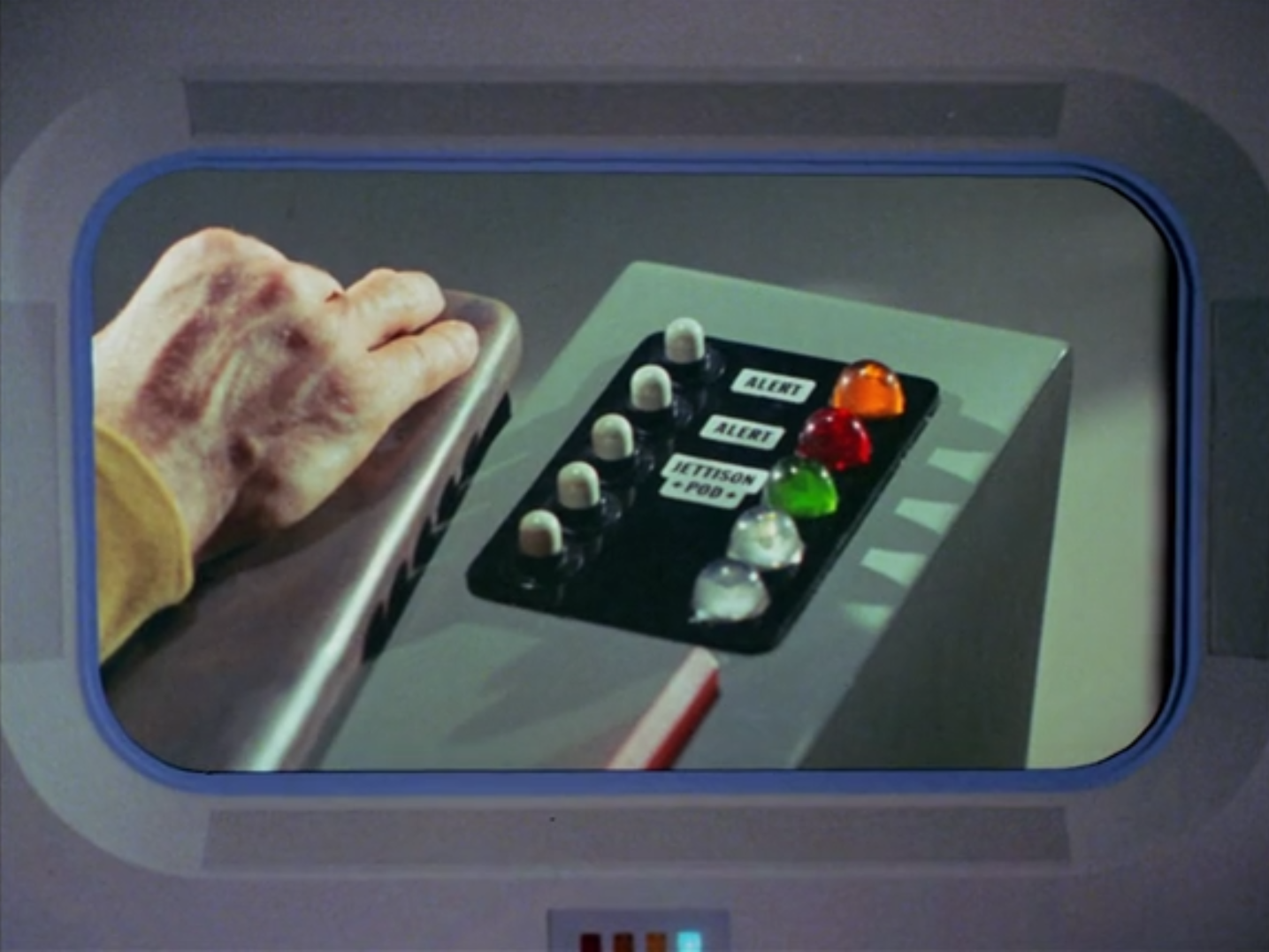

They decide they need to destroy all physical evidence of their presence, so Kirk and Sulu snoop around an Air Force base looking for computer tapes and film negatives. They get caught by an MP, who also gets accidentally beamed up to the Enterprise. Then Kirk is captured by the base commander. That one's quickly resolved, as Christopher, Spock, and Sulu beam down and rescue him.

At this point the episode's logic gets a bit fuzzy. Spock decides they can use the high-warp slingshot business to go forward in time too, and while time traveling, they use the transporter to swap Christopher and the MP for their past selves. Maybe this is its own little time loop, but I can't quite figure how. Regardless, the Enterprise makes it back to their present and Starfleet still exists, so whatever.

Commentary

I'm actually glad Star Trek opened the time travel box by appreciating its absurdity. This episode doesn't hold a candle to "Time's Arrow" (TNG 5x26/6x01) or "Trials and Tribble-ations" (DS9 5x06)—or The Voyage Home for that matter—but I still liked it.

Time travel is a strange narrative conceit. We'll get to look at a lot of different angles on it, from the deadly serious ("The City on the Edge of Forever," TOS 1x28), to pointed social commentary ("Past Tense," DS9 3x11/3x12), to the fascinating ("Year of Hell," VOY 4x08/4x09), to the heart-wrenching ("The Visitor," DS9 4x03), to just taking a long look at the road before and the road beyond ("All Good Things," TNG 7x25/7x26).

But right now we're having fun. So sit back and revel in it.

I will pose one question for you, though: Would the average zoomer recognize cellulose tape as computer memory or photographic film? What about people two hundred years in the future?

Setting aside stuff like Plan Nine and Manos and The Room and Birdemic, probably Star Trek XI, the one that JJ made. Splicing together test footage of Bela Lugosi and his chiropractor is one thing, but desecrating something beautiful is a sin.