Life expectancy in the country has now risen above the United States, to 78 years, from just 36 years at the time of the Communist revolution in 1949.

But China's retirement age remains one of the lowest in the world - at 60 for men, 55 for women in white-collar jobs and 50 for working-class women.

The plan to raise retirement ages is part of a series of resolutions adopted last week at a five-yearly top-level Communist party meeting, known as the Third Plenum.

this is clearly not true, Portal literally just got a huge fangame with a Steam release. the issue is entirely that it uses Nintendo stuff and the guy even says as much

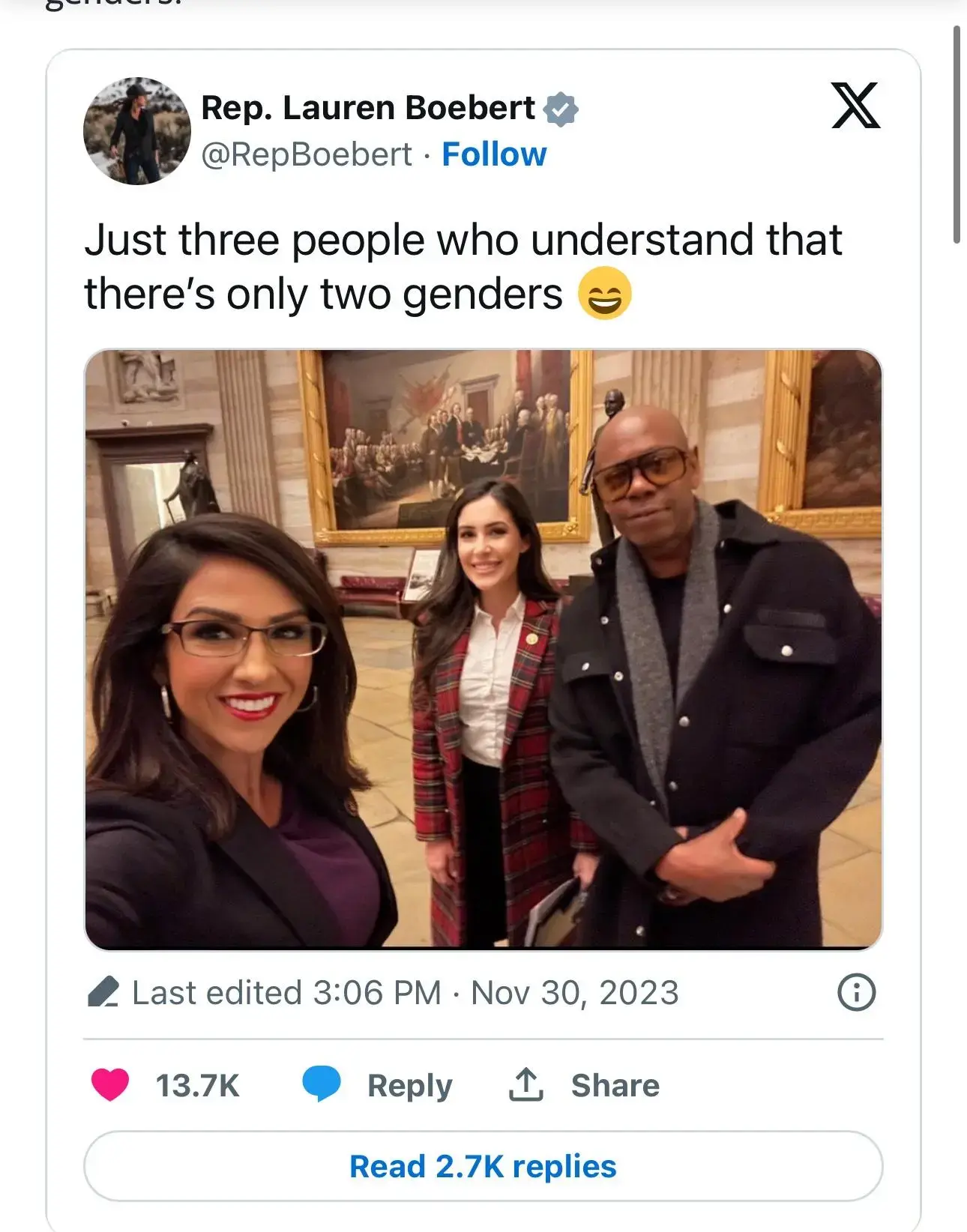

just to add to the plethora of responses: it rather defies belief that he's purely "joking" when, among other things, he's taken photos with anti-trans legislators like Lauren Boebert and let them frame those photos in this manner:

the weirdest thing to me is these guys always ignore that banning the freaks worked on Reddit--which is stereotypically the most cringe techno-libertarian platform of the lot--without ruining the right to say goofy shit on the platform. they banned a bunch of the reactionary subs and, spoiler, issues with those communities have been much lessened since that happened while still allowing for people to say patently wild, unpopular shit

techno-libertarianism strikes again! it's every few years with these guys where they have to learn the same lesson over again that letting the worst scum in politics make use of your website will just ensure all the cool people evaporate off your website--and Substack really does not have that many cool people or that good of a reputation to begin with.

Six months later, we can see that the effects of leaving Twitter have been negligible. A memo circulated to NPR staff says traffic has dropped by only a single percentage point as a result of leaving Twitter, now officially renamed X, though traffic from the platform was small already and accounted for just under two percent of traffic before the posting stopped. (NPR declined an interview request but shared the memo and other information). While NPR’s main account had 8.7 million followers and the politics account had just under three million, “the platform’s algorithm updates made it increasingly challenging to reach active users; you often saw a near-immediate drop-off in engagement after tweeting and users rarely left the platform,” the memo says.

the primary reason Hamas has political power and the political support to attack Israel in this manner is because Israel:

- treats all Palestinians as second-class citizens and subjects them to a system of political, social, and economic apartheid

- holds millions of Palestinians in squalid and inhuman conditions, and seizes the territory of millions more in the name of a violent settler project

- subjects the vast majority of Palestinians to state-sponsored discrimination, terror, indiscriminate bombing, and political violence

- leaves Palestinians no feasible democratic path to the rights they should have in their current state or the state of Israel, making armed struggle inevitable

you can and should condemn Hamas, but it is inarguable that Israel routinely does worse—overwhelmingly to people just as innocent as the ones Hamas is murdering—which is what makes attacks like this inevitable. you cannot do what Israel does and not expect the outcome to be violence, and it is incumbent on Israel, who holds all the actual power in this dynamic, to break the cycle and stop using every terrorist attack perpetuated against it as an excuse to roll innocent heads.

a core issue for moving wikis is that Fandom refuses to delete the old wiki so you 1) have to fight an SEO war against them; and 2) have to contend with directing everyone to the right place or else you have two competing wikis (one of which will gradually lapse out of date). it's very irritating.

i can only presume the remaining 5% is owned by NFTs Georg, who lives on the blockchain and is an outlier who should not have been counted

this is only your third comment on our site and you are not making a good impression by immediately getting offended by a pretty banal ask.

i fail to see why one being legal and one being illegal[^1] should have any bearing on the response or treating the people with basic human dignity. committing a crime also does not make one worthy of death--and especially not when that crime is one without a victim like illegal immigration.

[^1]: and i don't think the latter should be illegal (certainly not meaningfully so), to be clear. i am morally opposed to the idea of hard borders.

provided nothing else blocks it, this will once again go into effect starting in September.