When most people hear the name “Thor” (Þórr in Old Norse), it conjures up images of a powerful, hammer-wielding master of lightning and thunder. However, it may be surprising to learn that a direct connection between Thor and thunder does not appear anywhere in the Poetic Edda, our foremost source for Norse mythology. Throughout its pages Thor is never referred to as a thunder god, never explicitly causes a crash of thunder or a flash of lightning, and is called by no heiti that is indisputably thunder-related.

The Poetic Edda contains only a couple of hints that Thor might have anything to do with thunder. For instance, he is often referred to by the name Hlórriði which is hard to decipher but could plausibly be connected to thunder. Also, the mountains are said to tremble (fjöll öll skjalfa) in Lokasenna 55, when Thor arrives to confront and silence the troublesome Loki. We might assume that they shake at the sound of thunder, although thunder itself isn’t actually mentioned.

In the Prose Edda, the second of our two foremost sources for pagan Norse tales, this association is almost non-existent as well. Although Thor is a frequently recurring character in the (alleged) author Snorri Sturluson’s narratives, his own prose contains only one line in a section called Skáldskaparmál that mentions thunder in any kind of association with Thor. At the beginning of Thor’s epic duel with the giant Hrungnir Snorri states:

Því næst sá hann eldingar ok heyrði þrumur stórar. Sá hann þá Þór í ásmóði. Fór hann ákafliga ok reiddi hamarinn ok kastaði um langa leið at Hrungni.

And in English (transl. by me):

Thereupon he (Hrungnir) saw lightning and heard great thunder. He then saw Thor in god-like wrath. He (Thor) went forth furiously, and swung the hammer, and cast it from a long distance at Hrungnir.

But how do we know this thunderstorm has anything at all to do with Thor and isn’t just Snorri’s description of epic battle scenery? For that matter, with so little in the way of association between Thor and thunder in the Eddas, where exactly does the idea of Thor as a thunder god even come from?

Let’s start with etymology.

The name Þórr is derived from the reconstructed word *þunraz in an older language called Proto-Germanic that was mostly unwritten. The word *þunraz meant “thunder” and has descendant words in various Germanic languages apart from Old Norse. In fact, a lot of what we know about Proto-Germanic comes from comparing descendant languages to find inherited similarities.

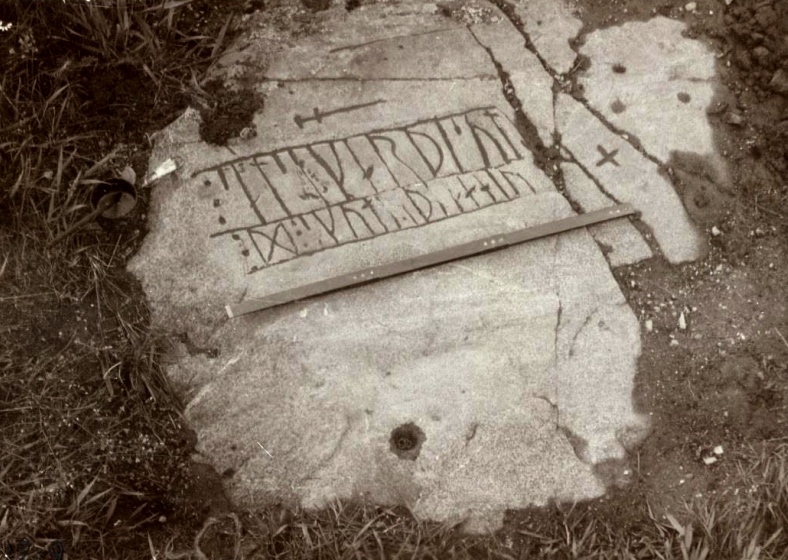

In Old English and Old High German, for example, the respective words þunor and donar are both descended from *þunraz and were both used to refer to the sound of thunder and also to a Thor-like deity. In Old English, the possessive form of þunor made its way into the word þunresdæg and eventually became “Thursday” in Modern English. The English Register of Oseney Abbey even shows Thursday being alternatively referred to as “þundurday” (literally “thunder day”) as late as 1490 in Middle English.

Interestingly, þruma, not þórr, is the Old Norse word for a clap of thunder. Its etymology is not entirely clear, but philologist and folklorist Jakob Grimm theorized that þruma could also be descended from the root in *þunraz by “metathesis of r, and change of n into m“, as Cleasby-Vigfusson summarized it. This is hard to verify, and would have been a pretty extreme linguistic evolution, but is also not entirely unheard of.

On the subject of difficult etymology, the name of Thor’s famous hammer, Mjǫllnir, may offer some interesting insights as well. In Dictionary of Northern Mythology, Rudolf Simek summarizes the historical debate about this word’s origin. “Earlier scholarship”, he says, connected it with Old Norse mala, meaning “to grind.” Others have made the obvious connection to Old Norse mjǫll, meaning “new snow” which evolved into Icelandic mjalli (“white color”) and may have, according to Simek’s summary, some connection to lightning as well. My personal favorite interpretation, which is admittedly not the most obvious but does provide a satisfying result, is a possible early borrowing from Old Slavic mlunuji (Russian molnija) which literally means “lightning” and would yield a definition of Mjǫllnir as “the one who makes lightning”.

But if we believe that Thor was so strongly associated with thunder based on etymology and hints from related Germanic mythology, why don’t we get a stronger association between Thor and thunder in the Eddas?

Declan Taggart notes that Thor is “a very flexible supernatural concept”. He theorizes that the unique conditions of Iceland, where the Eddas were written, may have caused Thor’s association with storms to become less prominent in that location. However, the broader association between Thor and thunder in ancient Scandinavia is made clearer through information provided by other authors and also via the odd skaldic poetry reference that does come from Iceland.

We have, for example, a stanza from Þórsdrápa, probably written by 10th century Icelandic skald Eilífr Goðrúnarson, referring to Thor as “the temple-steerer of the hovering chariot of the thunderstorm”.

To the east, in Denmark, a 12-13th century historian named Saxo Grammaticus authored a work called Gesta Danorum in which he sought to present an epic and illustrious history of the Danes. In Book 8, Saxo writes:

Thor, harassed by the giants’ insolence, had driven a burning ingot through the vitals of Geirrøth, who was struggling against him, and when this fell farther it had bored through and smashed the sides of the mountain; he confirmed that the women had been struck by the force of Thor’s thunderbolts and had paid the penalty for attacking his divinity by having their bodies broken.

– Gesta Danorum, Volume I; Karsten Friis-Jensen, Peter Fisher (transl.).

In Book 13, Saxo also provides his analysis of the origin of Thor’s famous hammer:

Now Magnus, too, emulated his vigorous pursuits with similar deeds of worth; among other distinctive trophies he had his followers bring back to his native country some unusually heavy implements known as Thor’s hammers, which were venerated by men of the primitive region on one of the islands. Ancient folk, in their desire to understand the causes of thunder, using an analogy from everyday life had wrought from a mass of bronze hammers of the sort they believed were used to instigate those crashes in the heavens, since they supposed the best way of copying the violence of such loud noises was with a kind of blacksmith’s tool.

Note that Saxo wrote his history in Latin. In the original text, the word written here as “Thor’s” is actually Iouiales, which is a form of an alternate name for the Roman god Jupiter.

Thor was often associated with both Hercules and Jupiter in ancient Latin texts by way of interpretatio romana, which was a method of interpreting the deities of various non-Roman peoples through the lens of the Roman pantheon. It is through the reverse process, interpretatio germanica, that the Germanic people came to associate Thor’s name with the same day of the week known in Latin as Iovis dies, “Day of Jove (Jupiter)”, a.k.a. Thursday. Thor’s association with thunder is evident again in this connection to Jupiter, who is another god famously tied to thunder.

The German chronicler Adam of Bremen living in the second half of the 11th century also provides a description of Thor’s position of prominence in a contemporary pagan temple at Uppsala. Alleging that his information comes from first-hand accounts, Adam states that:

Thor was the most powerful god and ruled over thunder and lightning, wind and rain, sunshine and crops. He sat in the centre with a hammer (Mjolnir) in his hand, and on each side were Odin, the god of war, in full armour and Frey, the god of peace and love, attributed with an enormous erect phallus.

– The History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen; Tschan (transl.)

Thor’s association with thunder is solidly apparent from a broad view. Many modern, North Germanic languages have even retained words for thunder incorporating Thor’s name. For instance, þórduna (Icelandic), tordön (Swedish), and torden (Danish and Norwegian) are all etymologically equal to “Thor’s din.” But the weakness of this association in our main sources for Norse myth is also fascinating.

A quick google search will probably yield a number of websites claiming that Thor’s common heiti Hlórriði means “the loud weather god” but this interpretation is not at all conclusive. Simek notes that this word is of “obscure etymology”, and “gives the impression of being an old cult name, but on the other hand it only occurs quite late” (p. 153). We are left to ponder on the fact that Thor clearly is a “loud weather god”, but interestingly, not so much in the Eddas.