Yes because mechanical fidelity is the lowest priority in continuing the series. Continuation of the story and tonal fidelity matter a lot more. The Fallout series went from a turn based 2.5D isometric RPG to a real time action RPG, and one of the best instalments in the series follows the latter formula.

WillOfTheWest

Same IP; returning characters from the original series; revisiting important locations from the original series; uses a D&D ruleset for resolution; expands upon the story of the Bhaalspawn crisis over a century after the incident, especially via the

spoiler

Dark Urge storyline.

All of this is apparent through playing the game.

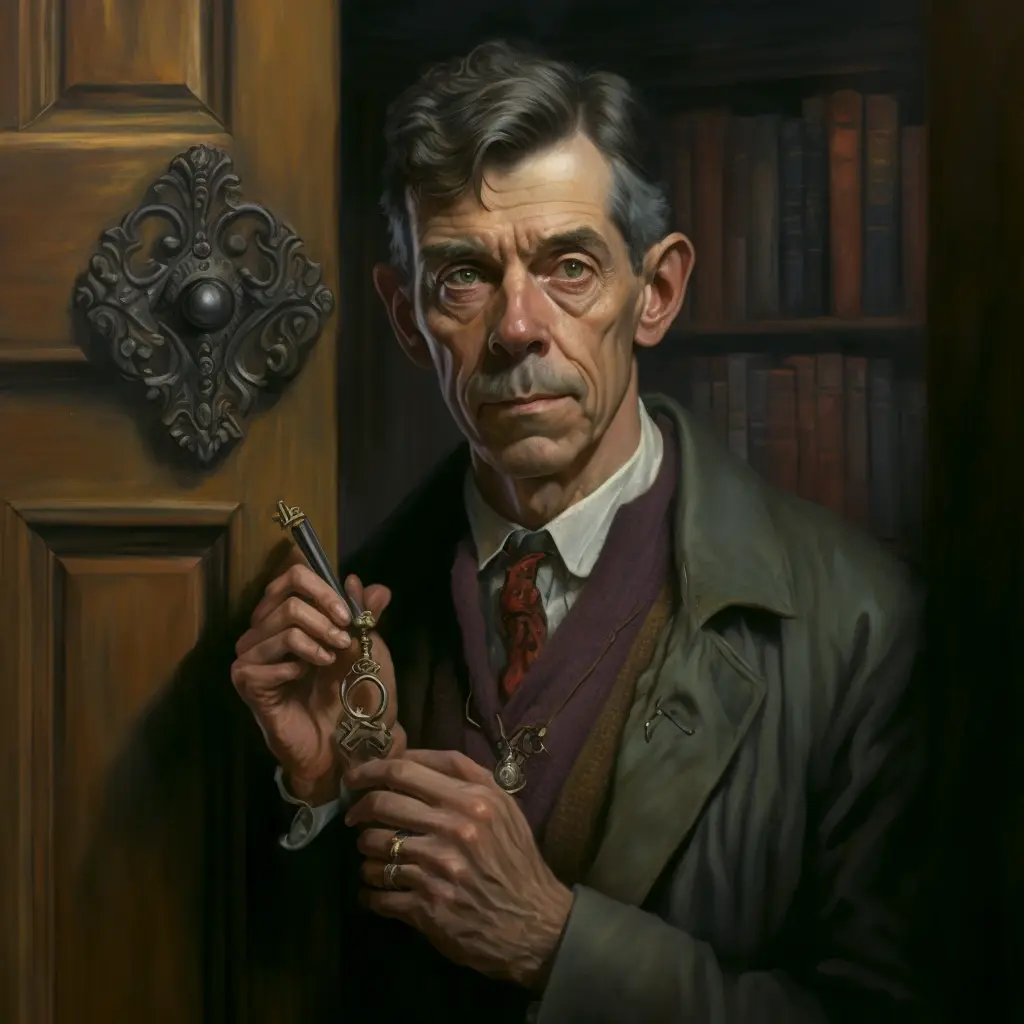

I definitely get the fever dream vibes. Especially early in his career, Lovecraft reported that some of his short stories were transcripts of his own dreams, written while not yet fully awake in order to keep the dream in his mind. I think perhaps this combined with his relative inexperience in writing contributed to his earlier stories being much shorter and often less coherent. I've often had amazing dreams that don't hold up against reflection in the cold light of day.

A common theme shared by this week's stories are vengeance; a cruel adversary who finds their comeuppance via disturbing and poetic means. I've looked up the background to these stories in preparation for this post and I notice that by 1919, Lovecraft had introduced himself to the works of Lord Dunsany. The text in these tales which have been referred to as Lovecraft's "dunsanian tales" is filled with references and nods to the fiction of Dunsany, who also wrote short stories based on the world of dreams.

In The Doom that Came to Sarnath we see another departure from a common trope of Lovecraft's stories, of disconnected gods mostly unaware or uncaring of the affairs of humans and other mere mortals. Though we are left with some questions unanswered, it is my interpretation that Bokrug, the patron god of the moon folk who dwelt in Ib, is the one who enacts vengeance on the people of Sarnath, on the 1000th anniversary of the razing of Ib.

At the time of the vengeance, the lore of the razing the city of Ib is long lost to all but the priesthood, and the annual celebration is little more than a ritual. Importantly, none of the noted deaths of the people of Sarnath are a consequence of violence; every single person was scared to death. This paints a picture of a patient and powerful entity, and an understanding of human psychology. Bokrug does not immediately stage a counter-assault and it does not use violence. Instead it secures the future of its followers by ensuring that the razing of Sarnath is never forgotten.

In The Cats of Ulthar we see plenty of ancient Egyptian imagery. The caravan paints humans with animal heads on the sides of their carts; the imagery of a disc in the space between horns is repeatedly used; and cats are referred to as the cousin of the Sphinx, "and he speaks her language, but he is more ancient that the Sphinx, and remembers that which she hath forgotten".

Upon his kitten being slaughtered, a little boy in the caravan utters a prayer and the caravan leaves. The following night, all of the cats of Ulthar have gone missing. There are dubious and contradicting reports that the caravaneers stole the cats, and that the cats were seen oddly encircling the house of the cat slayers, with one suggesting that the cat killers have somehow hypnotised the cats. In the morning the cats have miraculously returned, and all look fatter. Indeed, for many days the cats refuse food.

After a week with no news from the house of the cat killers, an investigating party wanders over only to find the clean picked bones of its two residents. The discovery is so chilling that the villagers pass a law that in Ulthar no man may kill a cat.

There is little ambiguity in what occurred here: the cats, bolstered by the power to which the boy prayed, are responsible for killing and consuming the two cat killers. Again this is evidence of the existence of patient patron deities who will enact brutal and unusual vengeance in order to ensure the survival of their favoured species. Considering also the reverent description of cats given in the first paragraph, this hints at mysteries in our world to which we as a whole remain clueless. This is actually a very common motif in Lovecraft's writing; that there are many secrets in our world to which mankind are ignorant. In other works he writes on how we are in fact blissfully ignorant, for the revelation of our position in reality will either cause us to go mad or regress to the ignorant safety of another dark age. Brilliant and chilling stuff.

I just go for completed series nowadays. It's just not worth the time ranting and actively waiting for the completion of certain series. I've made a conscious decision not to start on Rothfuss's trilogy until he finishes the final book.

I also find that recently I go for books with more mature themes; not gore- and sex-fests where everyone is morally grey for the sake of it, but stuff like Robin Hobb's books which explore feminism through a fantasy lens, or stories with characters who confront their flaws rather than being some ideal version of a character archetype.

In The White Ship we get our first glimpse of some of the geography of the Dreamlands. More interestingly we first see mention of godlike creatures other than the maddening Great Old Ones and Outer Gods. The eidolon Lathi rules over Thalarion, a city of Daemons and mad things which once were men.

The bearded man aboard the ship also mentions gods which are "greater than men, and they have conquered." The voyagers of the White Ship are guided to fantastical cities by a heavenly blue bird which seems to have suddenly appeared. It leads the voyagers to locations of increasing beauty and splendor, and each time the voyagers seek greater places. Ultimately, the bird leads the ship to its doom: a monstrous cataract where the waters of the world fall to abysmal nothingness. The watchman of this story closes his eyes and braces for the fall, only to wake at his old lighthouse.

Peering into the waters, he sees the remnant of a white ship, shattered on the rocks. Again this leads us to wonder: are Lovecraft's Dreamlands some mirror of our living world, or perhaps a physical space somehow connected to our world? Is there perhaps a more mundane explanation; are the dreamers simply dreaming of that which they may have perceived and then forgotten in the waking world? Could this inability to disassociate dream from reality merely be some form or madness?

I'm looking for community engagement without the homogenised superculture. I'd like to be able to discuss books on a small book community without someone jumping in with "I also choose this guy's dead wife" or "not my proudest fap" because it's a low effort way of garnering meta-points. I also like the lack of an account-based point system.

So far Lemmy is delivering and so I'm engaging here a lot more actively than I ever did on Reddit.

The site defaults to sorting by active posts. There are options for hot, new, and top over the past day. I tend to sort by new.

Baldur’s Gate is part of a setting several decades older than the game franchise of the same name. It was an official setting of D&D a decade before the first game. In the sense of a ROLEPLAYING game, fidelity to the source material is paramount.

The original games were developed at the end of the life cycle of the edition they used for the mechanics. The ruleset got a major revision the same year BG2 was released. There have been several major editions since. Edition warring aside, no one can argue that the Forgotten Realms played in 5th edition isn’t the same Forgotten Realms played in AD&D 2E. The tone and continued narrative of the setting is the key feature in maintaining the soul of a property, not mechanical fidelity.

The game respects the official canon of the Forgotten Realms, including the canonical ending to BG2 where Gorion’s Ward rejected divinity and eventually led to Bhaal’s revival. Characters from the original series return as companions for BG3, with stories acknowledging the Bhaalspawn crisis. One of the origin playthroughs is the exact same story as the first Baldur’s Gate.

If your only complaint is lack of real time with pause then I reckon it’s you who isn’t the real Baldur’s Gate fan.